By Erik Devaney

During the 19th-century, song-smiths in southern Appalachia, who had absorbed African rhythms from local slave populations, began fusing these rhythms with elements of celtic folk music, thus forming the basis of the country music genre.

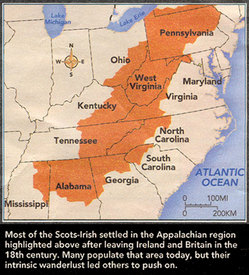

The influence of Celtic folk music in the South began before the start of the American Revolution. As early as 1717, waves of Scots-Irish immigrants were pouring into North America. By 1790, 3 million of these immigrants called America home. The Scots-Irish, also known as Scotch-Irish or Ulster-Scots, were Presbyterian Scots who had previously settled in Ulster as a result of Britain’s plan for a Protestant plantation in Ireland.

Separate waves of Scottish immigration to North America occurred starting in 1725 as a result of the Highland Clearances, while Irish Catholics would not arrive on the scene in great numbers until 1847: a result of the so called ‘famine‘. Despite their ideological differences, these Scottish and Irish immigrants shared a Celtic musical tradition, which employed many of the same techniques for playing, composing and arranging music. These techniques had a profound influence on that ‘country sound’ we are familiar with today.

Like their Celtic musician forefathers, country musicians often employ vocal harmonies in the choruses, or repeated portions, of songs. This strategy helps stress the importance and increase the forcefulness of the choruses while also separating them sound-wise from the verses. Check out the use of vocal harmonies in the choruses of Okie from Muskogee by Merle Haggard and compare it to the use of harmonies in the choruses of the Celtic song, Mairi’s Wedding, as performed by The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem.

If you find that some country or Celtic songs have hypnotic qualities to them, mesmerizing you as you listen, this phenomenon could be the result of a drone. A drone is a note or chord that sounds continuously throughout most, if not all, of a song, providing an underlying, trance-like accompaniment for the song’s melody. Musicians can create drones vocally or with virtually any pitch-controlled instrument. Country musicians, such as fiddlers and slide-guitarists, adopted droning from Scottish and Irish settlers, who were accustomed to producing drones with fiddles as well as bagpipes.

Listen for the drone in Fiddlin’ John Carson’s song, He Rambled, and compare it to the drone in the Scottish march, The Campbells Are Coming.

The Sob Story

Singing sorrowfully about the heartbreaks we suffer in life may not have been a distinctively Irish or Scottish creation, but Irish and Scottish immigrants certainly brought a tradition of sob stories with them when they showed up on the shores of Amerikay. Subject matter included longing for love (see Black Is The Colour), losing children (see The Wife of Usher’s Well) and leaving behind a troubled home only to encounter new troubles abroad (see By The Hush).

The Drinking Song

“Here’s to alcohol: the cause of, and solution to, all of life’s problems”

The use of the fiddle in country music pre-dates the use of the guitar. To clarify, a fiddle is, physically, the same instrument as a violin. The difference is perception: most classical violinists get offended when you call them fiddlers, as they consider fiddling to be an informal, inferior type of playing… what a bunch of jerks.

The use of the fiddle in country music pre-dates the use of the guitar. To clarify, a fiddle is, physically, the same instrument as a violin. The difference is perception: most classical violinists get offended when you call them fiddlers, as they consider fiddling to be an informal, inferior type of playing… what a bunch of jerks. The banjo does not have Celtic origins.

The banjo does not have Celtic origins.African slaves brought the tradition of building banjos with them when they were transported to the New World; a tradition that required stretching strings across animal-skin drums.

However, when musically-inclined inhabitants of the Appalachians got their hands on banjos, they used them to play the fiddle tunes that they had learned from the Scottish and Irish.

The plot thickens: in the 19th century, banjos crossed the Atlantic, for a second time, and musicians in Ireland and Scotland began incorporating the African/American instruments into traditional Celtic music. The The Dubliners are a great example of a Celtic folk band that adopted the banjo.

Further Reading:

Ceolas: Celtic Music Instruments

Thanks For The Music: The Fiddle in Country Music

BluegrassBanjo.org: History of the Banjo

Who Are The Scotch Irish?

Leave a comment